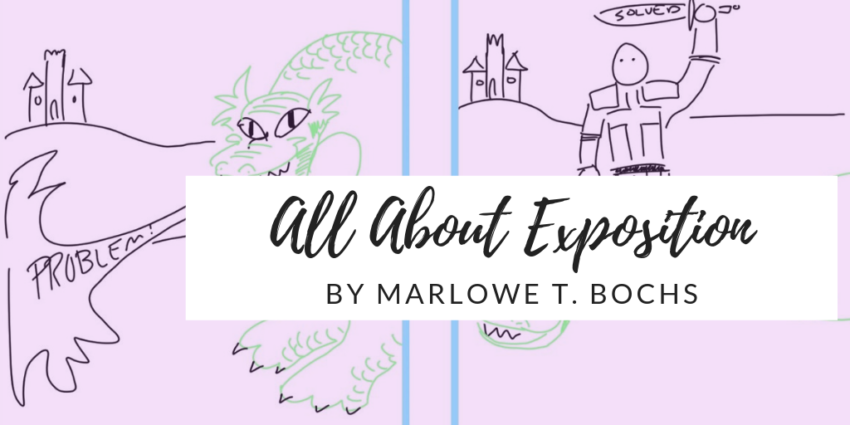

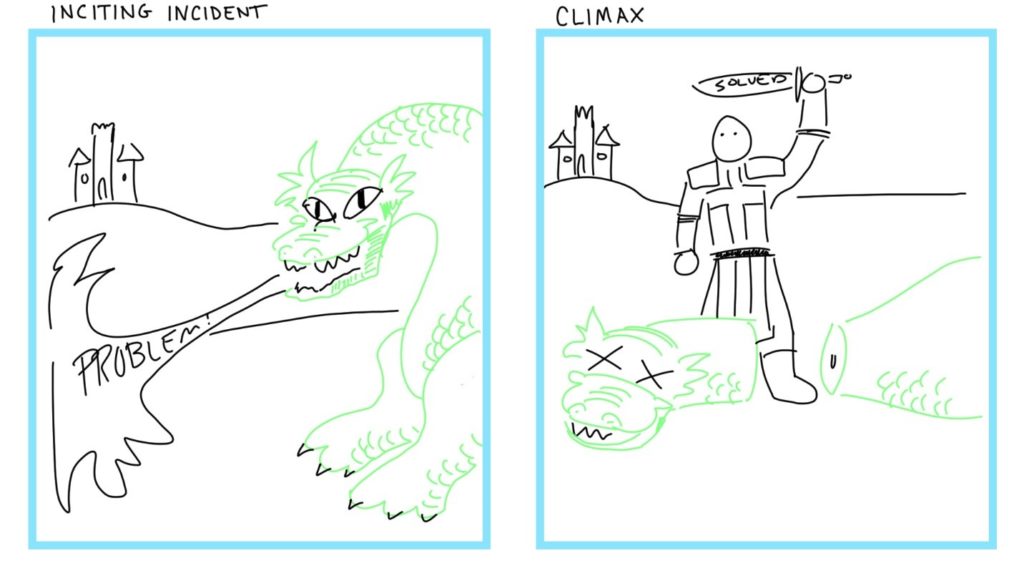

Last time, we discussed what a story is. A story is the life of a problem. It starts when the problem is first encountered and ends when the problem is solved. When the problem is first encountered, it’s called the inciting incident. When the problem is resolved, it’s called the climax.

However, the telling of the story doesn’t have to begin with the inciting incident. The telling of a story has a short amount of time to set the scene, to show where and to whom the problem will occur.

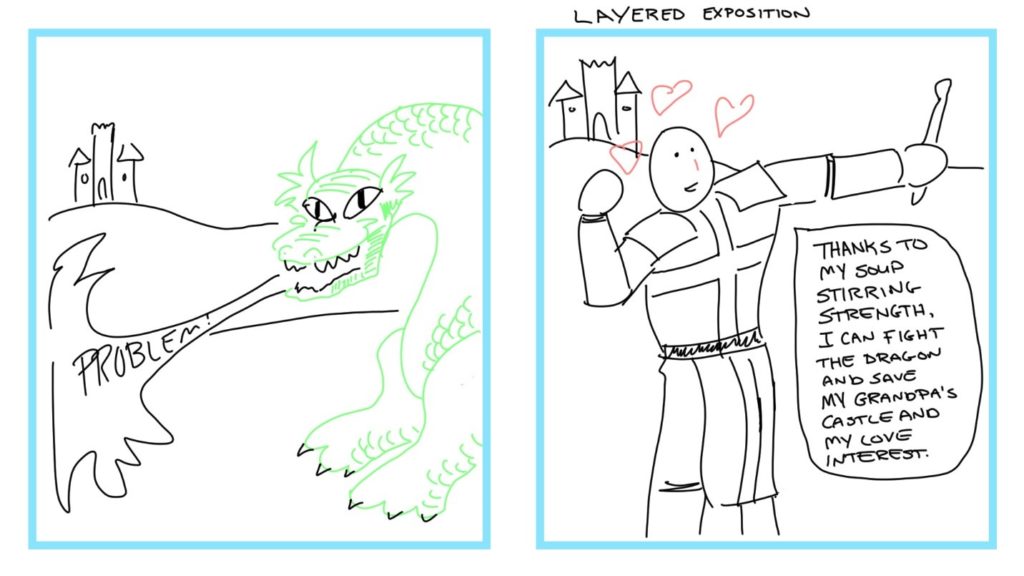

This preliminary part of a story is called the exposition.

The trouble with exposition is that it’s boring. Remember, story is the language of the brain. Your reader’s brain thrives on conflict. Most readers will hang around for a while to see if a conflict develops, but if it doesn’t arrive soon enough, they will leave unsatisfied.

In the past, when entertainment was rare and expensive, exposition was plentiful. Victorian novels might have chapters upon chapters of exposition. However, the modern reader has a million stories at their fingertips at any moment. They want the conflict to arrive as soon as possible. One simple solution is to invert the two elements. Jump into the story with the inciting incident and then backfill the exposition.

In this case, the tension of the problem has already been activated. The reader will hang around to see the resolution of that tension (the climax of that story). You can use that tension to hold their attention while you build your character and world.

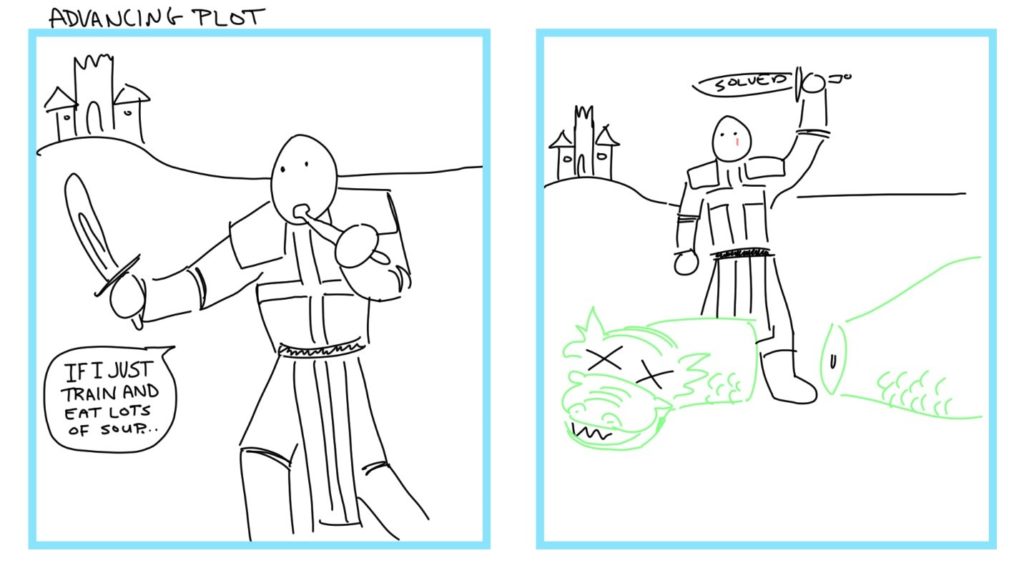

There are two main mistakes you can make at this point. The first is to pass up this opportunity. Tension is the engine of the story. When you have it, use it. Unless it’s a very short story, jumping from inciting incident to climax will feel slight and inconsequential. See the first story on this page for an example. We’ll discuss in the future how you can make this mistake even if you have content between the inciting incident and the climax.

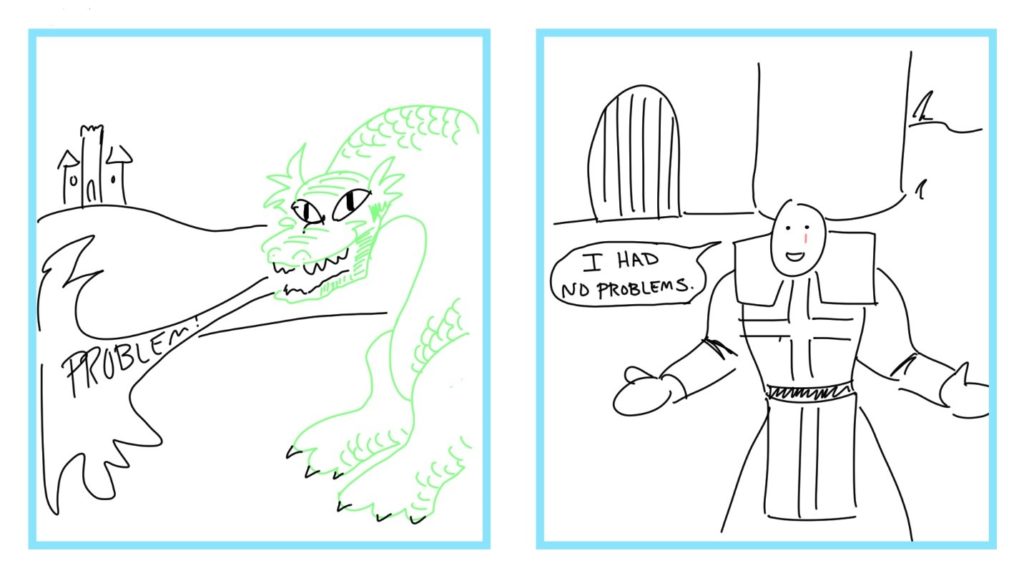

The other major error is to overindulge in your exposition. Readers want to know your character and your world, but only in the ways it relates to the conflict. If you introduce a dragon and then spend pages discovering the past and personality of the hero, in ways that don’t reflect dragon hunting, your reader will get angry (and not in the good way).

When exposition comes before the inciting incident, the space after is reserved for advancing plot. When you put the exposition after the inciting incident, it has to share space with advancing plot.

Takeaways:

- A story is the life of a problem. The moment the problem emerges is called the inciting incident. The moment it is solved is called the climax.

- There is tension in a story between the inciting incident and the climax. Tension keeps readers engaged.

- Exposition can be boring. One solution is to start the story at the inciting incident and then backfill the exposition.

- The Art of Storytelling: Rising Action - April 25, 2019

- All About Exposition - March 27, 2019

- What Is a Story? - March 19, 2019

I like the way you make it very simple to.understand.