We’ve covered conflict and exposition. Now it’s time for the rising action.

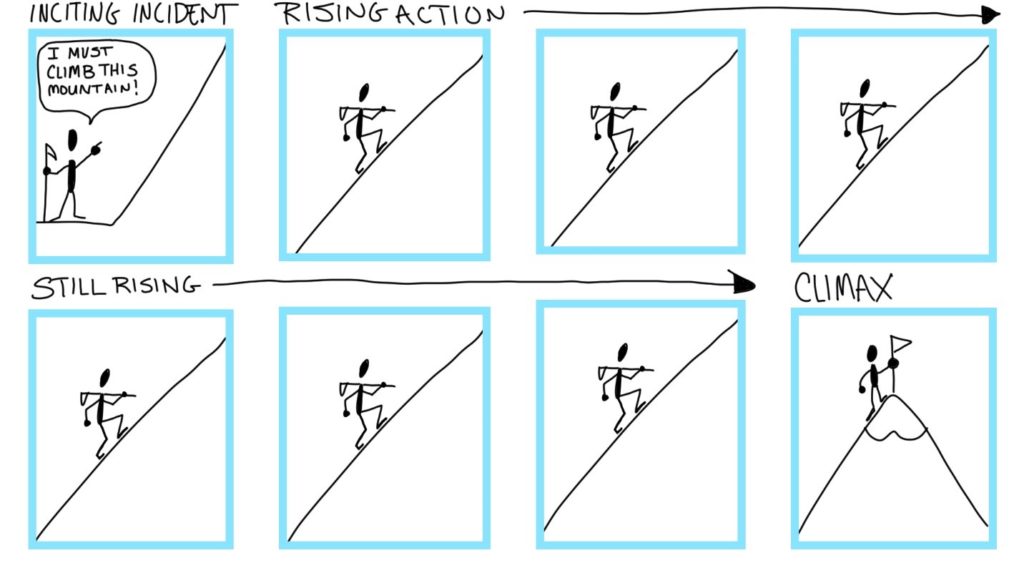

Rising action is the majority of the story. Everything that happens between the inciting incident (introduction of the problem) and the climax (solution to the problem) should be rising action.

What does rising action mean? It means that the events are moving toward the climax. If you want to summit a mountain, then every step you take toward the top of the mountain is rising action (quite literally in this case).

Your audience needs to see the problem solved, so they’ll sit through a lot of rising action if the central problem is compelling. However, they can get bored. If the solution is a foregone conclusion, or the rising action is never in doubt (as in the above example) then the audience will either quit the story (since they know the ending anyway) or skip to the end. You’ll have lost the story’s tension and the audience’s attention.

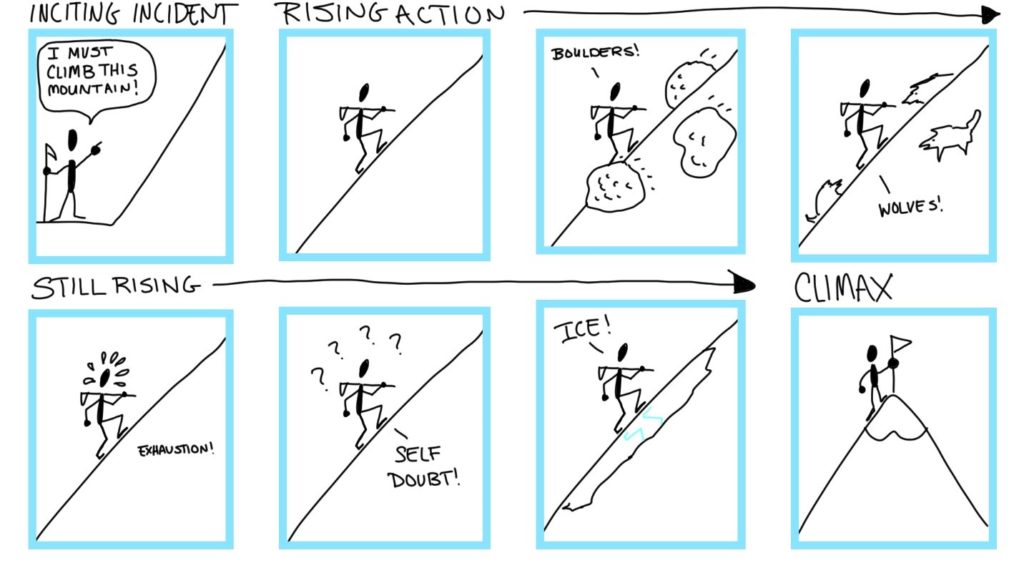

To maintain tension the conflict must act against the protagonist on a regular basis, so the climax is always in doubt.

This is a perfectly acceptable order for rising action. However, it may not be the ideal order. Once we get into discussing the best order we do enter a subjective discussion.

If we lead with self-doubt, we may kill the momentum off the inciting incident and create a character that’s unlikeable. If done right, leading with self-doubt could create a triumphant, kid-makes-good story.

Boulders and wolves, both being external conflicts, may be too close to each other in this version. Place them apart and make one inform the other and you may strengthen the story. For example, the protagonist learns to dodge from the boulders and then uses that skill, three scenes later to dodge the wolves. Now, in the two scenes feel connected both by type of conflict and solution, but are far enough away from each other in the story to not feel repetitive.

Take a moment to consider the above incidents. How might you reorder them for a better story? What other scenes could you add to this simple story to increase the drama?

This is the work of a storyteller, to engage the audience between the inciting incident and the climax.

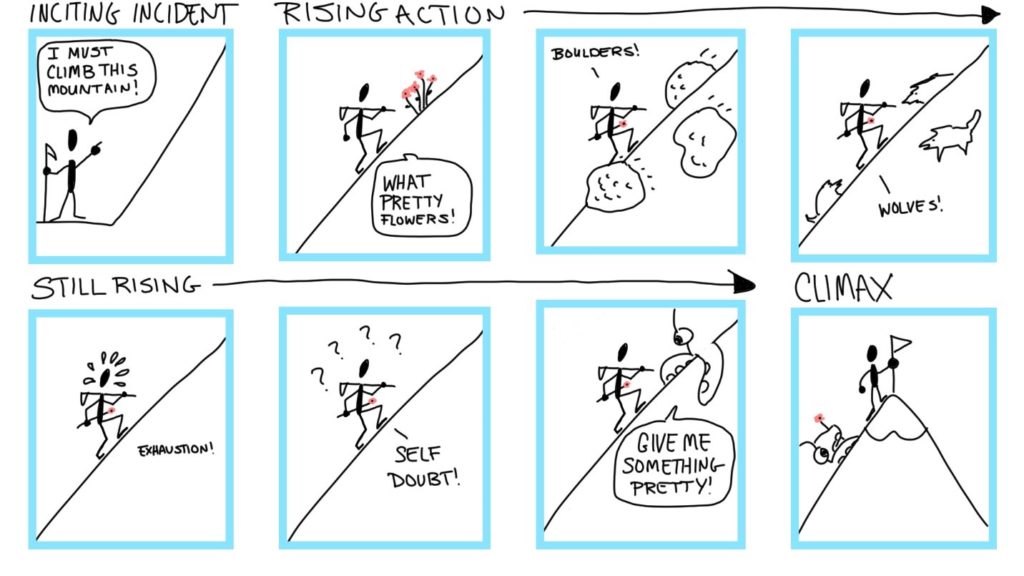

Before we go, here’s one easy trick to use. It’s called Checkov’s Gun.

A Chekhov’s gun is an object (or idea or ability) that the protagonist acquires early on that somehow aids in the final conflict. This is actually a poor example of a Chekhov’s gun. Chekov’s guns should ideally be non-obvious and hidden. Your audience should forget their significance until they come back at the end.

In the strictest sense a Chekhov’s gun should appear early, be somewhat forgotten and deemphasized, and then show-up again at the climax. However, a story with multiple conflicts may have multiple Chekhov’s guns.

Takeaways:

- Rising action is the meat of the story, everything that happens between the inciting incident and the climax.

- Rising action must move toward the climax and be varied in its presentation. If the rising action stalls or becomes predictable you will lose your audience.

- Chekov’s gun (hiding the solution to the conflict early in the rising action) is one simple trick for bringing a structure to a story.

- The Art of Storytelling: Rising Action - April 25, 2019

- All About Exposition - March 27, 2019

- What Is a Story? - March 19, 2019